SONO - dormir mal e pouco faz você engordar | SLEEP - sleeping poorly and little makes you fat

Se você quer perder massa gorda, quer emagrecer, tem uma boa alimentação, faz exercício físico e mesmo assim não está conseguindo emagrecer… talvez o seu problema seja o seu sono.

Hoje, sem sombra de dúvidas adultos e crianças inclusive dormem menos, comparado à algumas décadas atrás, isso devido a mudança abrupta de estilo de vida. Dormir o mínimo possível, é muitas vezes visto como um comportamento admirável na sociedade contemporânea, só que as pessoas se esquecem que o sono desempenha um papel importantíssimo na função neuroendócrina e no metabolismo da glicose.

Padrões de sono ruins, não dormir o suficiente tende a pessoa ganhar peso facilmente e também à um aumento no índice de massa corporal (IMC), só que esse aumento é de gordura.

A privação QUANTITATIVA e QUALITATIVA do sono irá fazer você acumular mais gordura no corpo, fará com que a pessoa tenha sonolência durante o dia, e isso vai prejudicar sua produtividade/rendimento que ficará lá embaixo.

E quando bate aquele sono na pessoa durante o dia, durante o trabalho, durante a atividade que ela está executando, falta de energia, fadiga… o que ela faz? Toma café. Só que ficar tomando café não é legal, café, contém cafeína, que é estimulante e fará com que você não durma direito, prejudica a qualidade do sono, e aí no dia seguinte a pessoa vai tomar mais café… vira um ciclo sem fim. Isso fará desencadear outras doenças.

A falta de sono pode levar a outras doenças mais sérias:

- imunidade reduzida

- infecções mais frequentes

- aumento de doenças

- picos de apetite -> compulsão alimentar

- maior consumo de calorias -> ganho de peso

- ganho de peso -> obesidade -> diabetes tipo 2 -> doenças cardiovasculares

- hipertensão

- obesidade

- doença arterial coronariana

- diabetes tipo 2

- pneumonia incidente

- afeta toda a parte cognitiva -> memória, raciocínio, tomada de decisões, mau humor, irritabilidade

- expectativa de vida mais curta

“No extremo, você pode morrer. No nível mais básico, as pessoas que não dormem o suficiente têm uma expectativa de vida mais curta até certo ponto” Dr. Rafael Pelayo, Clinical Professor, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences - Sleep Medicine, Univerdade de Standorf, California/USA.

“Se você privar alguém de sono, é mais provável que contraiam um vírus ou uma infecção e também não respondam tão bem às imunizações”. Pelayo

“Qualquer coisa que esteja errada com você física ou psicologicamente é agravada pela falta de sono”, continuou Pelayo. “Por exemplo, se você é propenso a enxaqueca, você terá enxaqueca pior se não dormir o suficiente. Qualquer coisa que você possa pensar é piorada por não dormir o suficiente.” Pelayo

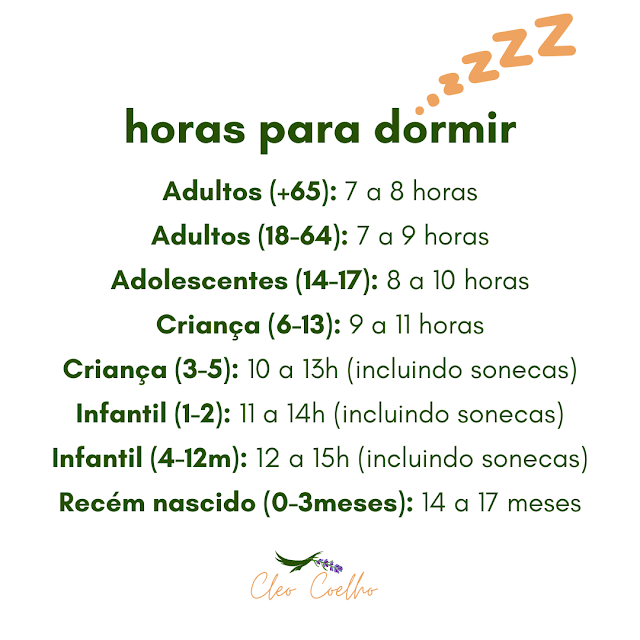

Quanto de sono devemos dormir?

Depende de cada faixa etária.

É importante ter uma boa noite de sono regularmente para uma regulação hormonal ideal. Isso inclui dormir o suficiente e profundamente o suficiente para entrar no sono de movimento rápido dos olhos (REM). O sono leve ou o sono interrompido com frequência não funcionará. Sono perdido, não é recuperado.

O sono é poderoso, é mágico, é onde acontece o processo de cura no nosso corpo. A falta de sono bagunça todo o nosso sistema de hormônios. Alguns hormônios só funcionam durante a noite, quando se está dormindo. Precisa dormir para a magia dos hormônios acontecerem. O sono limpa as toxinas do seu cérebro. É como uma limpeza de energia. O sono ruim causa estragos em sua bioquímica interna.

A baixa qualidade do sono ou a falta de sono podem perturbar o equilíbrio hormonal no corpo. A interrupção do equilíbrio hormonal ocorre se você não dormir o suficiente. Se seu corpo produz cortisol por mais tempo, isso significa que você está produzindo mais energia do que o necessário.

Hormônios como leptina e grelina, que são responsáveis pela regulação da fome/apetite, são afetados. A leptina tem ação inibitória à fome e a grelina tem ação estimulante à fome. Não dormindo bem, fará seu corpo produzir menos leptina e mais grelina. Consequências: aumento da fome, compulsão alimentar, maior ingestão calórica, aumento de peso, obesidade.

Você também pode estar pulando o tempo de cura e reparo que vem dos níveis de hormônio do crescimento durante o sono. Os hormônios GH e cortisol são regulados à noite, durante o sono.

A tolerância à glicose e a secreção de insulina também são moduladas pelo ciclo sono-vigília.

A propensão do sono e a arquitetura do sono são, por sua vez, controladas pela interação de dois mecanismos de manutenção do tempo no sistema nervoso central, ritmicidade circadiana (ou seja, efeitos intrínsecos do tempo biológico, independentemente do estado de sono ou vigília) e homeostase sono-vigília (ou seja, uma medida da duração da vigília prévia, independentemente da hora do dia).

A ritmicidade circadiana é uma oscilação endógena com período próximo de 24 horas gerada nos núcleos supraquiasmáticos do hipotálamo. A geração e manutenção de oscilações circadianas em neurônios SCN envolvem uma série de genes de relógio (incluindo pelo menos per1, per 2, per3, cry1, cry2, tim, clock, B-mal1, CKIε/δ), muitas vezes referido como 'canônico ', que interagem em um complexo ciclo de retroalimentação de transcrição/tradução.

A vigília prolongada resulta em níveis aumentados de adenosina extracelular, que em parte derivam da degradação de ATP, e os níveis de adenosina diminuem durante o sono. O antagonista do receptor de adenosina, a cafeína, inibe o SWA (SWA; potência espectral de EEG na faixa de frequência de 0,5 a 4 Hz). O SWA é considerado o principal marcador do sono homeostático de pressão.

Os principais mecanismos pelos quais os efeitos moduladores da ritmicidade circadiana e da homeostase sono-vigília são exercidos nos sistemas fisiológicos periféricos, incluem a modulação dos fatores de ativação e inibição hipotalâmicos que controlam a liberação de hormônios hipofisários e a modulação da atividade nervosa simpática e parassimpática.

O GH é um hormônio essencialmente controlado pela homeostase sono-vigília.Tanto em homens jovens quanto em homens mais velhos, existe uma relação “dose-resposta” entre SWS e liberação noturna de GH. Quando o período de sono é deslocado, o pulso principal de GH também é deslocado e a liberação noturna de GH durante a privação do sono é mínima ou francamente ausente. Esse impacto da pressão do sono no GH é particularmente claro em homens, mas também pode ser detectado em mulheres.

O perfil de cortisol de 24 horas é caracterizado por um máximo de manhã cedo, níveis decrescentes ao longo do dia, um período de níveis mínimos à noite e primeira parte da noite, também chamado de período quiescente, e um aumento circadiano abrupto durante o final da tarde, parte da noite. Manipulações do ciclo sono-vigília afetam minimamente a forma de onda do perfil de cortisol. O início do sono está associado a uma inibição de curto prazo da secreção de cortisol que pode não ser detectável quando o sono é iniciado pela manhã, ou seja, no pico da atividade corticotrópica. Os despertares (finais e durante o período de sono) induzem consistentemente um pulso na secreção de cortisol. O ritmo do cortisol é, portanto, controlado principalmente pela ritmicidade circadiana. Os efeitos modestos da privação do sono estão claramente presentes, como será mostrado abaixo.

Os perfis de 24 horas de dois hormônios que desempenham um papel importante na regulação do apetite, a leptina, um hormônio da saciedade secretado pelos adipócitos, e a grelina, um hormônio da fome liberado principalmente pelas células do estômago, também são influenciados pelo sono. O perfil de leptina humana depende principalmente da ingestão de refeições e, portanto, apresenta um mínimo matinal e níveis crescentes ao longo do dia, culminando em um máximo noturno. Sob nutrição enteral contínua, condição de ingestão calórica constante, observa-se uma elevação da leptina relacionada ao sono, independentemente do horário do sono. Os níveis de grelina diminuem rapidamente após a ingestão da refeição e então aumentam em antecipação à refeição seguinte. As concentrações de leptina e grelina são maiores durante o sono noturno do que durante a vigília. Apesar da ausência de ingestão alimentar, os níveis de grelina diminuem durante a segunda parte da noite, sugerindo um efeito inibitório do sono per se. Ao mesmo tempo, a leptina é elevada, talvez para inibir a fome durante o jejum noturno.

O cérebro é quase inteiramente dependente da glicose para obter energia e é o principal local de eliminação de glicose. Assim, não é surpreendente que grandes mudanças na atividade cerebral, como aquelas associadas às transições sono-vigília e vigília-sono, afetem a tolerância à glicose. A utilização de glicose cerebral representa 50% da eliminação total de glicose corporal durante o jejum e 20-30% pós-prandial. Durante o sono, apesar do jejum prolongado, os níveis de glicose permanecem estáveis ou caem apenas minimamente, contrastando com uma clara diminuição durante o jejum no estado de vigília. Assim, os mecanismos que operam durante o sono devem intervir para evitar que os níveis de glicose caiam durante o jejum noturno. Protocolos experimentais envolvendo infusão intravenosa de glicose a uma taxa constante ou nutrição enteral contínua durante o sono mostraram que a tolerância à glicose se deteriora à medida que a noite avança, atinge um mínimo em torno do meio do sono e depois melhora para retornar aos níveis matinais. Durante a primeira parte da noite, a diminuição da tolerância à glicose deve-se à diminuição da utilização da glicose tanto pelos tecidos periféricos (resultante do relaxamento muscular e rápidos efeitos hiperglicêmicos da secreção de GH no início do sono) quanto pelo cérebro, como demonstrado por estudos de imagem PET que mostraram uma redução de 30 a 40% na captação de glicose durante o SWS em relação à vigília ou ao sono REM. Durante a segunda parte da noite, esses efeitos diminuem, pois o sono leve não REM e o sono REM são dominantes, os despertares são mais prováveis de ocorrer, o GH não é mais secretado e a sensibilidade à insulina aumenta, um efeito retardado dos baixos níveis de cortisol durante a noite e início da noite. Esses importantes efeitos moduladores do sono nos níveis hormonais e na regulação da glicose sugerem que a perda do sono pode ter efeitos adversos na função endócrina e no metabolismo.

Obesidade

- Dados epidemiológicos apoiam consistentemente uma ligação entre sono curto e risco de obesidade.

- Estudos epidemiológicos em adultos também mostraram associações entre sono curto e risco de diabetes

Um número crescente de crianças obesas e pode sofrer de apneia obstrutiva do sono. O impacto desse distúrbio do sono, que é conhecido por promover resistência à insulina e redução da testosterona em adultos, na liberação neuroendócrina e na função metabólica em crianças.

Agora que você sabe de tudo isso, você vai perder uma boa noite de sono?

* * *

If you want to lose fat, you want to lose weight, you have a good diet, you exercise and you still can't lose weight… maybe your problem is your sleep.

Today, without a doubt, adults and children even sleep less, compared to a few decades ago, due to the abrupt change in lifestyle. Getting as little sleep as possible is often seen as an admirable behavior in contemporary society, but people forget that sleep plays a huge role in neuroendocrine function and glucose metabolism.

Poor sleep patterns, not getting enough sleep tends to gain weight easily and also to an increase in body mass index (BMI), only this increase is fat.

QUANTITATIVE and QUALITATIVE sleep deprivation will make you accumulate more fat in the body, make the person drowsy during the day, and this will harm your productivity / income that will be down there.

And when the person gets sleepy during the day, during work, during the activity they are performing, lack of energy, fatigue… what does they do? Drink coffee. It's just that drinking coffee isn't cool, coffee contains caffeine, which is a stimulant and will make you not sleep well, impair the quality of sleep, and then the next day the person will drink more coffee… it becomes an endless cycle. This will trigger other diseases.

Lack of sleep can lead to other, more serious illnesses:

- reduced immunity

- most frequent infections

- increase in disease

- appetite spikes -> binge eating

- higher calorie consumption -> weight gain

- weight gain -> obesity -> type 2 diabetes -> cardiovascular disease

- hypertension

- obesity

- coronary artery disease

- type 2 diabetes

- incident pneumonia

- affects the whole cognitive part -> memory, reasoning, decision making, bad mood, irritability

- shorter life expectancy

How much sleep should we sleep?

It depends on each age group.

Sleep vs Hormones:

It's important to get a good night's sleep regularly for optimal hormone regulation. This includes sleeping enough and deeply enough to enter rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Light sleep or frequently interrupted sleep will not work. Lost sleep is not regained.

Sleep is powerful, it's magical, it's where the healing process takes place in our body. Lack of sleep messes up our entire hormone system. Some hormones only work at night, when you are sleeping. You need sleep for the hormone magic to happen. Sleep cleanses your brain of toxins. It's like an energy cleanse. Bad sleep wreaks havoc on your internal biochemistry.

Poor sleep quality or lack of sleep can upset the hormonal balance in the body. Disruption of hormonal balance occurs if you don't get enough sleep. If your body produces cortisol longer, it means you are producing more energy than you need.

Hormones such as leptin and ghrelin, which are responsible for regulating hunger/appetite, are affected. Leptin has a hunger-inhibiting action and ghrelin has a hunger-stimulating action. Not sleeping well will make your body produce less leptin and more ghrelin. Consequences: increased hunger, binge eating, higher caloric intake, weight gain, obesity.

You may also be skipping the healing and repair time that comes from growth hormone levels during sleep. GH and cortisol hormones are regulated at night, during sleep.

Glucose tolerance and insulin secretion are also modulated by the sleep-wake cycle.

Sleep propensity and sleep architecture are, in turn, controlled by the interaction of two time-maintaining mechanisms in the central nervous system, circadian rhythmicity (i.e., intrinsic effects of biological time, regardless of sleep or wakefulness state). and sleep-wake homeostasis (ie, a measure of the duration of previous wakefulness, regardless of the time of day).

Circadian rhythmicity is an endogenous oscillation with a period close to 24 hours generated in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus. The generation and maintenance of circadian oscillations in SCN neurons involves a number of clock genes (including at least per1, per 2, per3, cry1, cry2, tim, clock, B-mal1, CKIε/δ), often referred to as ' canonical', which interact in a complex transcription/translation feedback loop.

Prolonged wakefulness results in increased levels of extracellular adenosine, which in part stem from ATP degradation, and adenosine levels decrease during sleep. The adenosine receptor antagonist caffeine inhibits SWA (SWA; spectral power of EEG in the frequency range 0.5 to 4 Hz) [7]. The SWA is considered the main marker of pressure homeostatic sleep.

The main mechanisms by which the modulatory effects of circadian rhythmicity and sleep-wake homeostasis are exerted on peripheral physiological systems include the modulation of hypothalamic activating and inhibiting factors that control the release of pituitary hormones and the modulation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity.

GH is essentially a hormone controlled by sleep-wake homeostasis. In both young and older men, there is a “dose-response” relationship between SWS and nocturnal GH release. When the sleep period is shifted, the main pulse of GH is also shifted and nocturnal GH release during sleep deprivation is minimal or frankly absent. This impact of sleep pressure on GH is particularly clear in men, but it can also be detected in women.

The 24-hour cortisol profile is characterized by an early morning high, decreasing levels throughout the day, a period of low levels in the evening and early evening, also called the quiescent period, and an abrupt circadian rise during the late night. afternoon, part of the night. Manipulations of the sleep-wake cycle minimally affect the waveform of the cortisol profile. Sleep onset is associated with a short-term inhibition of cortisol secretion that may not be detectable when sleep is initiated in the morning, that is, at the peak of corticotropic activity. Arousals (late and during the sleep period) consistently induce a pulse in cortisol secretion. Cortisol rhythm is therefore primarily controlled by circadian rhythm. The modest effects of sleep deprivation are clearly present, as will be shown below.

The 24-hour profiles of two hormones that play an important role in appetite regulation, leptin, a satiety hormone secreted by adipocytes, and ghrelin, a hunger hormone released primarily by stomach cells, are also influenced by sleep. The human leptin profile depends primarily on meal intake and therefore shows a morning minimum and increasing levels throughout the day, culminating in a nighttime maximum. Under continuous enteral nutrition, condition of constant caloric intake, a sleep-related elevation of leptin is observed, regardless of sleep time. Ghrelin levels decrease rapidly after eating the meal and then increase in anticipation of the next meal. Leptin and ghrelin concentrations are higher during nocturnal sleep than during wakefulness. Despite the absence of food intake, ghrelin levels decrease during the second part of the night, suggesting an inhibitory effect of sleep per se. At the same time, leptin is elevated, perhaps to inhibit hunger during overnight fasting.

The brain is almost entirely dependent on glucose for energy and is the main site of glucose elimination. Thus, it is not surprising that major changes in brain activity, such as those associated with sleep-wake and sleep-wake transitions, affect glucose tolerance. Brain glucose utilization represents 50% of total body glucose elimination during fasting and 20-30% postprandial. During sleep, despite prolonged fasting, glucose levels remain stable or fall only minimally, in contrast to a clear decrease during fasting in the waking state. Thus, mechanisms operating during sleep must intervene to prevent glucose levels from dropping during overnight fasting. Experimental protocols involving intravenous glucose infusion at a constant rate or continuous enteral nutrition during sleep have shown that glucose tolerance deteriorates as the night progresses, reaches a minimum around mid-sleep, and then improves to return to morning levels. During the first part of the night, the decrease in glucose tolerance is due to a decrease in glucose utilization by both peripheral tissues (resulting from muscle relaxation and rapid hyperglycemic effects of GH secretion at sleep onset) and by the brain, as demonstrated by PET imaging studies that showed a 30-40% reduction in glucose uptake during SWS compared to wakefulness or REM sleep. During the second part of the night, these effects subside as light non-REM sleep and REM sleep are dominant, awakenings are more likely to occur, GH is no longer secreted, and insulin sensitivity increases, a delayed effect. of low cortisol levels during the night and early evening. These important sleep-modulating effects on hormone levels and glucose regulation suggest that sleep loss may have adverse effects on endocrine function and metabolism.

Obesity

Insufficient sleep and sleep disturbances can affect pubertal development and growth, despite the fact that it has been known for several decades that the release of sex steroids and GH is markedly dependent on sleep during the pubertal transition.

An increasing number of children are obese and may suffer from obstructive sleep apnea. The impact of this sleep disorder, which is known to promote insulin resistance and reduced testosterone in adults, on neuroendocrine release and metabolic function in children.

It's important to get a good night's sleep regularly for optimal hormone regulation. This includes sleeping enough and deeply enough to enter rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Light sleep or frequently interrupted sleep will not work. Lost sleep is not regained.

Sleep is powerful, it's magical, it's where the healing process takes place in our body. Lack of sleep messes up our entire hormone system. Some hormones only work at night, when you are sleeping. You need sleep for the hormone magic to happen. Sleep cleanses your brain of toxins. It's like an energy cleanse. Bad sleep wreaks havoc on your internal biochemistry.

Poor sleep quality or lack of sleep can upset the hormonal balance in the body. Disruption of hormonal balance occurs if you don't get enough sleep. If your body produces cortisol longer, it means you are producing more energy than you need.

Hormones such as leptin and ghrelin, which are responsible for regulating hunger/appetite, are affected. Leptin has a hunger-inhibiting action and ghrelin has a hunger-stimulating action. Not sleeping well will make your body produce less leptin and more ghrelin. Consequences: increased hunger, binge eating, higher caloric intake, weight gain, obesity.

You may also be skipping the healing and repair time that comes from growth hormone levels during sleep. GH and cortisol hormones are regulated at night, during sleep.

Glucose tolerance and insulin secretion are also modulated by the sleep-wake cycle.

Sleep propensity and sleep architecture are, in turn, controlled by the interaction of two time-maintaining mechanisms in the central nervous system, circadian rhythmicity (i.e., intrinsic effects of biological time, regardless of sleep or wakefulness state). and sleep-wake homeostasis (ie, a measure of the duration of previous wakefulness, regardless of the time of day).

Circadian rhythmicity is an endogenous oscillation with a period close to 24 hours generated in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus. The generation and maintenance of circadian oscillations in SCN neurons involves a number of clock genes (including at least per1, per 2, per3, cry1, cry2, tim, clock, B-mal1, CKIε/δ), often referred to as ' canonical', which interact in a complex transcription/translation feedback loop.

Prolonged wakefulness results in increased levels of extracellular adenosine, which in part stem from ATP degradation, and adenosine levels decrease during sleep. The adenosine receptor antagonist caffeine inhibits SWA (SWA; spectral power of EEG in the frequency range 0.5 to 4 Hz) [7]. The SWA is considered the main marker of pressure homeostatic sleep.

The main mechanisms by which the modulatory effects of circadian rhythmicity and sleep-wake homeostasis are exerted on peripheral physiological systems include the modulation of hypothalamic activating and inhibiting factors that control the release of pituitary hormones and the modulation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve activity.

GH is essentially a hormone controlled by sleep-wake homeostasis. In both young and older men, there is a “dose-response” relationship between SWS and nocturnal GH release. When the sleep period is shifted, the main pulse of GH is also shifted and nocturnal GH release during sleep deprivation is minimal or frankly absent. This impact of sleep pressure on GH is particularly clear in men, but it can also be detected in women.

The 24-hour cortisol profile is characterized by an early morning high, decreasing levels throughout the day, a period of low levels in the evening and early evening, also called the quiescent period, and an abrupt circadian rise during the late night. afternoon, part of the night. Manipulations of the sleep-wake cycle minimally affect the waveform of the cortisol profile. Sleep onset is associated with a short-term inhibition of cortisol secretion that may not be detectable when sleep is initiated in the morning, that is, at the peak of corticotropic activity. Arousals (late and during the sleep period) consistently induce a pulse in cortisol secretion. Cortisol rhythm is therefore primarily controlled by circadian rhythm. The modest effects of sleep deprivation are clearly present, as will be shown below.

The 24-hour profiles of two hormones that play an important role in appetite regulation, leptin, a satiety hormone secreted by adipocytes, and ghrelin, a hunger hormone released primarily by stomach cells, are also influenced by sleep. The human leptin profile depends primarily on meal intake and therefore shows a morning minimum and increasing levels throughout the day, culminating in a nighttime maximum. Under continuous enteral nutrition, condition of constant caloric intake, a sleep-related elevation of leptin is observed, regardless of sleep time. Ghrelin levels decrease rapidly after eating the meal and then increase in anticipation of the next meal. Leptin and ghrelin concentrations are higher during nocturnal sleep than during wakefulness. Despite the absence of food intake, ghrelin levels decrease during the second part of the night, suggesting an inhibitory effect of sleep per se. At the same time, leptin is elevated, perhaps to inhibit hunger during overnight fasting.

The brain is almost entirely dependent on glucose for energy and is the main site of glucose elimination. Thus, it is not surprising that major changes in brain activity, such as those associated with sleep-wake and sleep-wake transitions, affect glucose tolerance. Brain glucose utilization represents 50% of total body glucose elimination during fasting and 20-30% postprandial. During sleep, despite prolonged fasting, glucose levels remain stable or fall only minimally, in contrast to a clear decrease during fasting in the waking state. Thus, mechanisms operating during sleep must intervene to prevent glucose levels from dropping during overnight fasting. Experimental protocols involving intravenous glucose infusion at a constant rate or continuous enteral nutrition during sleep have shown that glucose tolerance deteriorates as the night progresses, reaches a minimum around mid-sleep, and then improves to return to morning levels. During the first part of the night, the decrease in glucose tolerance is due to a decrease in glucose utilization by both peripheral tissues (resulting from muscle relaxation and rapid hyperglycemic effects of GH secretion at sleep onset) and by the brain, as demonstrated by PET imaging studies that showed a 30-40% reduction in glucose uptake during SWS compared to wakefulness or REM sleep. During the second part of the night, these effects subside as light non-REM sleep and REM sleep are dominant, awakenings are more likely to occur, GH is no longer secreted, and insulin sensitivity increases, a delayed effect. of low cortisol levels during the night and early evening. These important sleep-modulating effects on hormone levels and glucose regulation suggest that sleep loss may have adverse effects on endocrine function and metabolism.

Obesity

- Epidemiological data consistently support a link between short sleep and obesity risk.

- Epidemiological studies in adults have also shown associations between short sleep and diabetes risk.

Insufficient sleep and sleep disturbances can affect pubertal development and growth, despite the fact that it has been known for several decades that the release of sex steroids and GH is markedly dependent on sleep during the pubertal transition.

An increasing number of children are obese and may suffer from obstructive sleep apnea. The impact of this sleep disorder, which is known to promote insulin resistance and reduced testosterone in adults, on neuroendocrine release and metabolic function in children.

Instagram: @nutricleocoelho

Fontes | research source:

https://www.healthline.com/health-news/why-poor-sleep-can-lead-to-weight-gain

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2770720?guestAccessKey=79997185-38d6-472f-b8f7-c5b8434f4700&utm_source=For_The_Media&utm_medium=referral&utm_campaign=ftm_links&utm_content=tfl&utm_term=091420

https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/how_much_sleep.html

https://www.sleepfoundation.org/physical-health/weight-loss-and-sleep

https://www.healthline.com/health-news/why-poor-sleep-can-lead-to-weight-gain#Tips-for-better-sleep

https://www.healthline.com/health/sleep/how-sleep-can-affect-your-hormone-levels#sleep-tips

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3065172/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1389945713011520?via%3Dihub

https://stanfordhealthcare.org/doctors/p/rafael-pelayo.html

https://www.healthline.com/health/healthy-sleep#how-much-sleep-do-you-need?

https://www.healthline.com/health/natural-sleeping-remedies

Comentários

Postar um comentário